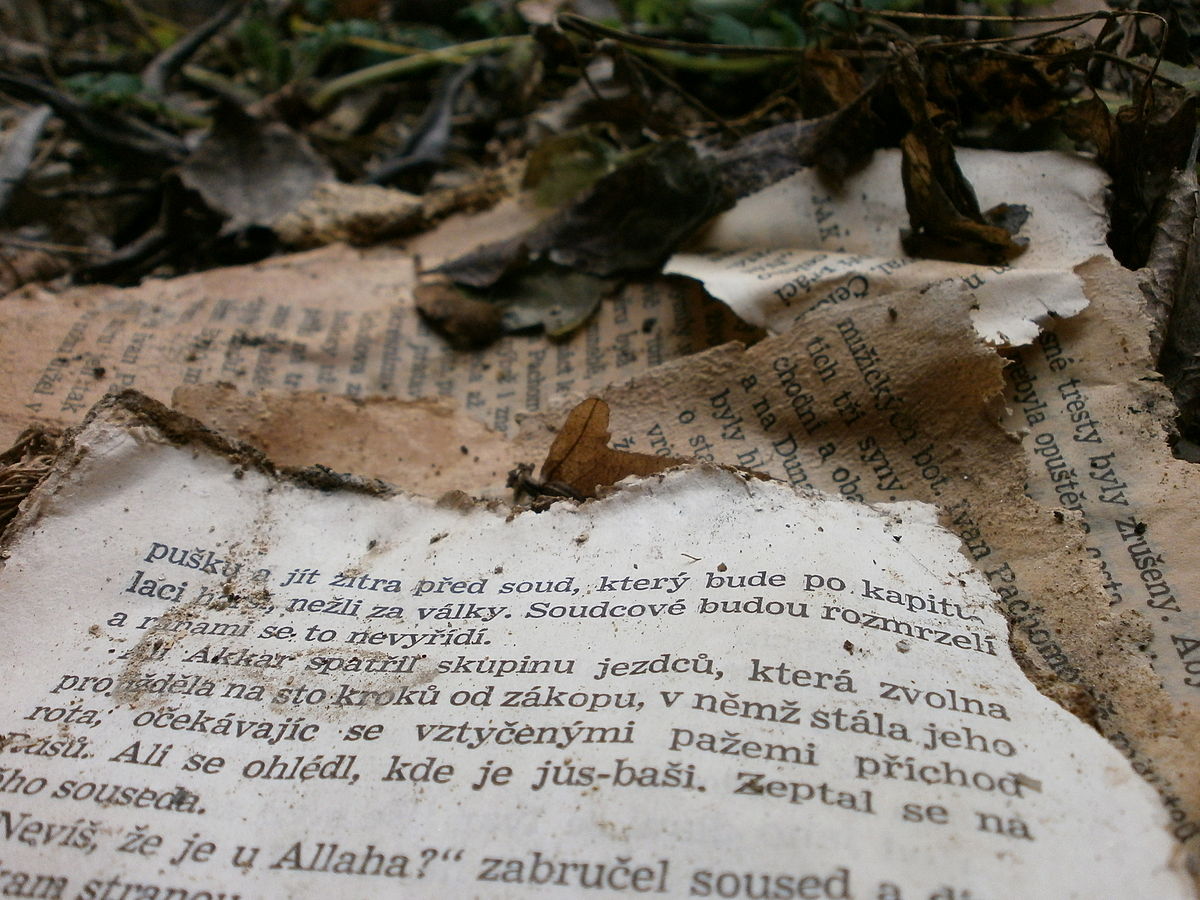

Left in the rain! A favorite book—ruined.

It was a growing-up experience for many book lovers, accidentally ruining a prized book. And how does it feel? The feeling is sadness, but also moral guilt.

I’ve been writing about the concept of “goodness,” and today I would like to look at a special aspect of goodness: morality.

How do we make moral judgments? These are judgments not on objects, but on personal character. As we judge objects by how they affect the needs of our own lives, so we may judge people.

Moral judgment points specifically to that aspect of a person which is in his own control—his choices. We do not judge a plague victim to be evil. But a thief is evil. Though a thief may bring less harm to others, we consider him guilty because he had a choice in the matter.

Morality applies only to the realm of choice. To call a man morally good or evil is to make a very far-reaching judgment about what kind of actions he will take in the future—to help life, or to harm it.

Early in life, a child learns to make moral judgments of other people. Whereas a baby judges only by pleasure or displeasure, a young child can hold others to standards.

As a child matures, he eventually notices that moral judgments apply to him too. Consider the careless child who ruined his favorite book. He knows he has lost a value by his own poor choice. He has not even hurt another person, but morality applies to him in isolation. He knows he has destroyed a value, and he feels self-contempt.

The negative feeling diminishes over time, especially if the child resolves to take a lesson from the experience.

But what happens when a person does not resolve to face the facts and do better? Over time, such a person becomes a threat to himself and to everyone around him. Others must judge him as morally bad. This means 1) he will hurt himself, and 2) he will hurt others.

The first and second points are connected. The kind of person who does not face facts and who does not act based on the needs of life—that person is a danger to everyone. Conversely, the moral qualities that enable a man to prosper are the very qualities that will benefit others.

I conclude that, whether we judge ourselves or others, the standard of moral goodness is the same one we apply to evaluating objects—

The standard is life—human life.